| Power Classification | 7P reclassified 8P in 1951 |

| Introduced | 1935 – 1938 |

| Designer | Gresley |

| Company | LNER |

| Weight – Loco | 109t 19cwt |

| Tender | 60t 7cwt – corridor tender 64t 19cwt |

| Driving Wheels | 6ft 8ins |

| Boiler Pressure | 250psi superheated |

| Cylinders | Three – 18½in x 26in – some had the inside cylinder reduced to 17in x 26in |

| Tractive Effort | 35,4550lbf – 33,616lbf with reduced inside cylinder |

| Valve Gear | Walschaert with derived motion (piston valve) |

In the early 1930s the LNER was considering providing high speed services between London and Newcastle. At first the possibility of a diesel-electric train was considered, based on the German Flying Hamburger train.

In May 1933, the German State Railways diesel-electric Fliegende Hamburger entered service, with long stretches of 85mph required by the scheduled timetable. Gresley travelled on the Fliegende Hamburger and was impressed by the need for streamlining, although he realised it was only useful at the highest speeds.

It was decided to use conventional rolling stock with streamlined steam propulsion as the diesel units of the time did not have the desired passenger carrying capacity and the capital investment in the new technology was prohibitive. Gresley set about producing an engine which would meet the requirements.

He was sure that steam could do the job equally well and with a decent fare-paying load behind the locomotive and so, following trials in 1935 with one of his A3 pacifics 2750 Papyrus, which recorded a new maximum of 108 mph and completed the journey between London and Newcastle in under four hours, the LNER’s Chief General Manager Ralph Wedgwood took the initiative, authorising Gresley to produce a streamlined development of the A3 locomotive.

The first of the new A4 class engines was named Silver Link and it was completed at Doncaster in 1935. It was a development of his A3 class, but it was greatly altered in appearance.

This wedge-shaped streamlining on the A4 was inspired by a Bugatti rail-car which Gresley had observed in France. The design was refined with the help of Prof. Dalby and the wind tunnel facilities at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) at Teddington. As well as streamlining, it was important that the design lifted smoke up away from the cab. At first, there was a lot of difficulty in achieving this. During the wind tunnel tests, it was noticed that a thumb print had inadvertently been added to the plasticine model, just behind the chimney. Only on impulse, was the model re-tested with the thumb print. Amazingly, the smoke was lifted well clear of the cab.

The application of internal streamlining to the steam circuit, higher boiler pressure and the extension of the firebox to form a combustion chamber all contributed to a more efficient locomotive than the A3; consumption of both coal and water were reduced.

The first four engines (2509-2512, later 60014-60017) were painted silver and hauled the new Silver Jubilee (The new service was named in celebration of the 25th year of King George V’s reign) train between London and Newcastle in only four hours. A demonstration run from Kings Cross to Grantham on 27th September 1935 touched 112.5mph. The first service was on the 1st October 1935, hauled by 2509 Silver Link. The Silver Jubilee was designed as a complete streamlined train including streamlined coaches. These had valences between the bogies and flexible covers over the coach ends. Although this restricted their use, it maximised the streamlining effects and proved useful for publicity. The train had capacity for 198 passengers on 7 coaches: twin-articulated brake third, triple-articulated restaurant set, and a twin-articulated first class.

The engines proved successful and more were added in 1936-1939. They proved able to handle the fastest trains on the East Coast Main Line, and ran smoothly at speeds over 100mph.

By the Autumn of 1937 the LNER had four of its A4 locomotives painted silver-grey for working the Silver Jubilee, five in garter -blue for working the Coronation express and the rest painted the LNER standard apple green. In October 1937 a further two engines in blue livery were required to work The West Riding Limited. The need to segregate locomotives for different deployment became untenable and the silver locomotives were repainted blue and all future engines carried the blue livery.

Although the Second World War did not start until 3rd September 1939, the last streamlined services ran on 31st August 1939 due to the enactment of the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939. In those early days, services were seriously cut back, and the evacuation trains had started. Over the next few months, many services returned but timetables were generally much slower than before the war. Freight took priority, and both blackout conditions and lack of maintenance took their toll on Britain’s railways.

Initially the Kings Cross A4s were put into storage, although the other A4s were kept in service. Eventually all of the Kings Cross A4s returned to service. Generally, the A4s were called upon to pull loads much heavier than originally intended. They did this well, although reduced maintenance produced some problems especially with the conjugated gear. To aid maintenance, Thompson removed the side skirts (valences) that were designed by Oliver Bulleid from the A4s. Because the A4s were experiencing much increased loads, they occasionally had problems starting off. To help with this Thompson had the valve gear modified so that a maximum of 75% cut-off was possible. Only 6 locomotives were converted during wartime, with the remainder being converted between 1946 and 1957.

A rather weird wartime change, was the removal of most of the chime whistles. It was thought that these might be confused with air-raid sirens. These were removed in 1942 and destroyed. New chime whistles were built after the war.

In the summer of 1948, BR performed a series of locomotive trials, comparing the different classes of the Big Four companies. The A4s produced some good results and had the lowest coal and water consumption figures of any of the expresses. Unfortunately, there were three A4 failures – all related to the conjugated motion. These are thought to have been due to poor wartime maintenance as the conjugated motion worked well if it received good maintenance.

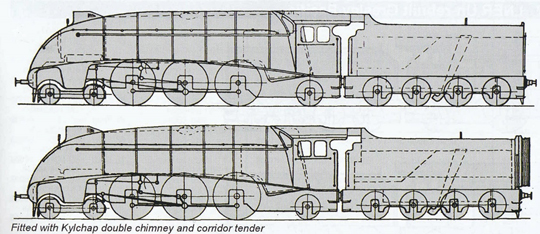

Four engines (later 60005 Sir Charlew Newton, 60022 Mallard, 60033 Seagull and 60034 Lord Faringdon) were built with Kylchap plast-pipes and double chimneys which considerably improved the running at high speeds, the rest having single chimneys. It was found that the economy obtained over the single chimney A4s was from six to seven pounds of coal per mile, which more than justified the expense of the conversion. Eventually the whole class was rebuilt by BR with double chimneys and modified middle big ends (to overcome persistent problems with the big ends over-running).

The A4 Class locomotives were known affectionately by train spotters as streaks.

Most engines of the class were fitted with corridor tenders to allow a change of crew on long non-stop runs.

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, maintenance of the locomotives and the permanent way improved, so facilitating speed increases of the A4s. Pre-war speeds were never reached, although in 1959, 60007 Sir Nigel Gresley set a post-war steam speed record of 112mph. By the late 1950s, steam was being replaced by diesel power. Although the Deltics proved worthy successors of the A4s on East Coast Mainline express services, other diesel classes were generally very poor and often failed. Hence, the A4s were kept in service until the mid-1960s.

In August 1948 very heavy rain caused the the line between Berwick and Dunbar to be breached in ten places. This was a particular problem for the non-stop trains between Edinburgh and kings cross which had only been re-introduced in May 1948. Whilst the alternative route to bypass the damaged area was only 16 miles longer there was no water throughs and also the route included a section with a gradient of 1 in 70 where the load for an unassisted pacific locomotive was 400 tons. The answer was that water had to be provided at Galashiels. The result was that the change in route added 70 minutes to the scheduled time. On 24th August a Haymarket crew on 60029 Woodcock hauling a load of 435 tons chose not to stop for water and set a new world record non-stop run of 408.6 miles. This feat was achieved on a further sixteen occassions during that summer. The record stayed until August 1989 when 60103 Flying Scotsman covered 422 miles non-stop whilst running between Melbourne and Alice Springs in Australia. Flying Scotsman was though running with two tenders to provide additional water capacity.

In 1951 K J Cooke was moved by Riddles from Swindon to take charge of the Eastern and north eastern as regional Mechanical Engineer. Whilst the erecting shops at Doncaster were capable of constructing the largest and most powerful locomotives the facilities were such that the frame alignment was not as exacting as at Swindon or even Crewe. To compensate for this the greater clearance had to be allowed in the working parts. At Swindon Cook had been used to using the Zeiss optical system for lining up frames, cylinders and main axle bearings and he introduced a similar system at Doncaster. This was then used on the pacific locomotives when they were overhauled and this resulted in improved working of the engines.

The first A4s were scrapped at the end of 1962. These were from Kings Cross and had been directly replaced by the Deltics. Several A4s saw out their remaining days until 1966 in Scotland, particularly on the Aberdeen – Glasgow express trains, for which they were used to improve the timing from 3.5 to 3 hours. The last BR A4 service was on 14th September 1966 between Aberdeen and Glasgow.

Number in Service.

| Built | Withdrawals | No. in Service | ||

| BR Numbers | Quantity | |||

| 1935 | 60014-17 |

4 |

4 |

|

| 1936 | 60023-24, |

2 |

6 |

|

| 1937 | 60003-4, 7-13, 18-20 & 25-31 |

19 |

25 |

|

| 1938 | 60001-2, 5-6, 21-22 & 32-34 |

9 |

34 |

|

| 1938 | LNER 4496 |

1 |

35 |

|

| 1939-41 |

35 |

|||

| 1942 | LNER 4496 |

1 |

34 |

|

| 1943-61 |

34 |

|||

| 1962 |

5 |

29 |

||

| 1963 |

10 |

19 |

||

| 1964 |

7 |

12 |

||

| 1965 |

6 |

6 |

||

| 1966 |

6 |

0 |

||

Locomotive allocations during British Railways operation

|

Depot as of January |

1948 | 1955 | 1964 | 1965 |

1966 |

| Aberdeen Ferryhill |

8 |

9 |

6 |

||

| Gateshead |

8 |

8 |

4 |

||

| Grantham |

10 |

||||

| Haymarket (Edinburgh) |

7 |

7 |

1 |

||

| Kings Cross |

9 |

19 |

|||

| St Margarets (Edinburgh) |

4 |

2 |

|||

| St Rollox (Glasgow) | 2 |

1 |

|||

|

34 |

34 | 19 | 12 |

6 |

|

The A4 locomotives were allocated to work the Glasgow to Aberdeen in 1962 after a successful trial in February of that year with 60027 Merlin. Employing them allowed the journey time to be reduced by thirty minutes and saved a number class members being employed on freight duties or withdrawn from service. Interestingly on the Glasgow Aberdeen runs they were crewed by London Midland & Scottish Region crews.

World Steam Record

Gresley realised that increased locomotive speeds meant longer braking distances. In order to source a more effective braking system he arranged for the trials with the Westinghouse system which was being used by his rivals on the LMS. In July 1938 the Westinghouse team arrived at London,s Wood Green depot to find Mallard steamed up and attached to a LNER dynamometer car to record the speed and three twin sets of carriages from the luxury Coronation service. At the outset the true purpose of the run which was to set a new world speed record was kept secret from the footplate crew.

In June 1937 the LMS has set a new world speed record when Coronation class 6220 achieved 114mph whilst hauling the Coronation Scot. This greatly upset Gresley who was further frustrated the following day when only 109mph was achieved going down Stoke bank on the LNER.

The scene was thus set for a trail run in July 1938 hauled by Mallard with the aim of establishing a new world speed record for a steam locomotive.

It should be remembered that the official speed limit was 90mph and it is a widely held view that not even the civil engineer was aware of the attempt on the record as it is by no means certain that he would have given permission for it to go ahead.

The outward journey undertook a series of ordinary brake tests at speeds of 90-100mph.

The trip ended at Barkston South where where the true nature of the run was explained to the crew. It was thought that a good run from Barkston would allow Mallard to climb Stoke Bank at a good speed and be able to attempt the world speed record on the downward gradient.

The train set off at 4:15pm but due to a dead slow restriction the train passed through Grantham at around 20mph.

By Stoke signal box, the speed had reached 74.5mph with full regulator and 40% cut-off. At milepost 94, 116mph was recorded along with the maximum drawbar of 1800hp. 120mph was achieved between milepost 92.75 and 89.75, and for a short distance of 306 yds, 125mph was touched.

After this the train was slowed down and after Essendine station was passed at a speed of 108mph a distinctive odour was noticed by the engine crew when the big end ran hot. When the train stopped at Peterborough it was found that the white metal had melted to an extent that it nearly wrecked the locomotive.

The news of the record run spread very quickly and Gresley thought that 130mph would be possible but further such runs were stopped by the outbreak of the Second World War.

A peak of 126mph was marked on the dynamometer rolls, and this speed was included in some unofficial reports. 126mph is also the speed marked on the plaque BR mounted on Mallard in 1948. Gresley never accepted this speed of 126mph, and thought it misleading. The LNER only claimed a peak average of 125mph – so breaking the world record for steam traction held by the German State Railways (124.5mph) and the British record set by the LMS (114mph).

Close analysis of the dynamometer roll (currently at the NRM) of the record run confirms that Mallard’s speed did in fact exceed that of the German BR 05 002. The Mallard record reached its maximum speed on a downhill run and actually failed technically in due course, whereas 05 002’s journey was on level grade and the engine did not yet seem to be at its limit. On the other hand the German train was only four coaches long (197 tons), but Mallard’s train was seven coaches (240 tons). One fact that is often ignored when considering rival claims is that Gresley and the LNER had just one serious attempt at the record, which was far from a perfect run with a 15 mph permanent way check just North of Grantham. Despite this a record was set. Gresley planned to have another attempt in September 1939, but this was prevented by the outbreak of World War II.Prior to the record run on 3 July 1938, it was calculated that 130 mph was possible, and in fact Driver Duddington and LNER Inspector Sid Jenkins both said they might well have achieved this figure if they not had to slow for the Essendine junctions.

At the end of Mallard’s record run, the middle big end (part of the motion for the inside cylinder) was found to have run hot (indicated by the bursting of a heat-sensitive “stink bomb” placed in the bearing for warning purposes), the bearing metal having melted, which meant that the locomotive had to stop at Peterborough rather than continue on to London. Deficiencies in the alignment of the Gresley-Holcroft derived motion meant that the inside cylinder of the A4 did more work at high speed than the two outside cylinders – indeed on at least one occasion this led to the middle big end wearing to such an extent that the increased piston travel knocked the ends off the middle cylinder – and this overloading was mostly responsible for the failure.

Accidents & Incidents

In April 1942 4469 received repairs at Doncaster Works and was temporarily allocated to Doncaster shed for running in on local services before returning to Gateshead. It was stabled at York North Shed on the night of 28/29 April 1942 when York station and North Shed were bombed during the attack by German aircraft.

4469 Sir Ralph Wedgwood and another nearby engine, B16 class 925 were damaged after a bomb fell through the shed roof and exploded between the two engines.

The A4 locomotive was severely damaged as a result of the explosion, but was recovered and towed to Doncaster shortly afterward. Due to the degree of damage, it was considered impractical to rebuild it and therefore 4469 was condemned and later scrapped.

The tender was retained and was later attached to a Thompson A2 pacific 60507 Highland Chieftain.

The tender attached to 4469 was stored at Doncaster until 1945, when it was then rebuilt and attached to LNER Thompson Class A2/1 3696 Highland Chieftain.

A new set of nameplates were made in 1944 and fitted to A4 4466, formerly named Herring Gull, and which carried these plates until withdrawn as British Railways 60006 on 3 September 1965.

A plaque was placed on the spot where 4469 was destroyed in 1942, now within the Great Hall of the National Railway Museum at York in 29 April 1992 to mark the 50th anniversary of the raid.

|

60031 Golden Plover on Perth shed-July 1965. 60031 spent its working life under BR based in Scotland-at Haymarket (Edinburgh) and then St Rollox (Glasgow) from where it was withdrawn from service in October 1965. I assume it was being stored at Pert when I saw it. It was scrapped in February 1966.

60027 Merlin takes the Waverley route route of Carlisle with a goods train-August 1965. 60027 was another Scottish based A4. It was based at St Margarets (Edinburgh) from September 1964 until it was withdrawn from service in the month after I took this photograph. It was scrapped in February 1966. |

Preservation

- 60007 Sir Nigel Gresley (LNER 4498, LNER 600, LNER 7 & BR 60007)

- 60008 Dwight D Eisenhower (LNER 4496, LNER 598, LNER 8 & BR 60008)

- 60009 Union of South Africa (LNER 4488, LNER 590, LNER 9 & BR 60009)

- 60010 Dominion of Canada (LNER 4489, LNER 591, LNER 10 & BR 60010)

- 60019 Bittern (LNER 4464, LNER 603, LNER 19 & BR 60019)

- 60022 Mallard (LNER 4468, LNER 707, LNER 22 & BR 60022)